Report from the Border

All other images are property of Sue Ellen Davis.

My wife and I just returned from a trip to the U.S./Mexico border at Brownsville. The purpose of the trip was to see firsthand how immigrants are being treated and how our law enforcement agencies and judicial system are performing.

Our trip was arranged through Texas Impact and The Texas Interfaith Center for Public Policy . This organization is hosting those who wish to volunteer and personally witness what is happening. The tour is called “Courts and Ports.”

Our group consisted of 4 couples. Our group was led by Cindy and Mike Johnson of Brownsville. Cindy and Mike are retired school teachers who have been very active in the volunteer community in Brownsville since their retirement. Their mission has been to do what they can to help reduce the suffering of migrants and to guide visitors to places and people that now play a key role in the immigration system and the lives of immigrants.

First, let me say that Cindy and Mike are two of the most passionate, caring, knowledgeable, devoted and energetic people I have ever met. We were with them from late Sunday afternoon until late Tuesday night. They answered endless questions. They took us to place after place in the Brownsville and Matamoros area to give us tours and they introduced us to the volunteers doing the hard work in each place. They feed the hungry. They buy medicine for the sick. They never lose their enthusiasm for helping the immigrants or allow themselves to become pessimistic about what can be accomplished by volunteers. Considering how long and hard they have worked in difficult circumstances, they are heroes.

Our visit to the area of downtown Brownsville that abuts the bridge to Matamoros gave me the impression we were visiting a military zone. There is, of course, a fence along the river. The fence is not “big and beautiful” unless you think razor wire is pretty. Below the fence is a road. Several border patrol vehicles drove past along this road during the short time we were near the fence. There is no fence on the Mexican side.

Cindy & Mike had put together several bags full of necessities to take across into Mexico. Each of us picked up as many reusable shopping bags and backpacks as we could carry and headed for the bridge. Mike also carried a container of dried beans and a container of uncooked rice. We intended to buy medicines from a farmacia in Mexico based upon a list of medicines provided by other volunteers.

Getting across the bridge costs $1 in quarters paid on the U.S. side. When you return, you pay .30 on the Mexican side. You are not allowed to take pictures of the security measures in place on the U.S. side of the bridge. There were very few pedestrians walking into Mexico. There was a very, very long line of people waiting to get into the U.S. on foot and by car. Since we were citizens with passports, we did not have to wait in line to return.

When we reached the Mexican shore, you have to show your identification and you may be asked to put your packages through an X-ray machine like those found in an airport. The security building on the Mexican side is in poor condition and not at all busy. There were very few security guards on the Mexican side. We saw no vehicles pass from the U.S. into Mexico at this bridge. Many years ago when I passed over this bridge to hunt in Mexico, the Mexican side was bustling with activity and vehicles. That is no longer true. The business area near the bridge is a shadow of its former self. We didn’t go far from the bridge, but you get the feeling that the downtown businesses on both sides of the border have been decimated by the lack of tourists and suffocated by the security. Considering the hassle the Mexicans have to endure in crossing and the crime in Matamoros, it is no wonder the economy has been hurt.

Once we were through security, we walked to the left side of the bridge. There we found a tent-city. These are small tents about waist high. They are camping tents which appear to be large enough to comfortably sleep two or, at most, 3 people. The edge of one tent is abutted by the edge of the next tent. The tents are not all alike and we were told the tents had been donated. There are also plain blue lightweight tarps strung on a rope. It appears the tent-city has been informally divided into 2 sections. There is a “medical tent” (a tarp overhanging a table and chairs) in each section. We dropped our supplies at these stations.

There is a security fence which runs along the left side of the camp. It is obvious that the tent-city has expanded beyond the fence and onto the bluff which overlooks the river.

We are told that there are around 2000 men, women and children living in this tent-city and that it is growing. That estimate looked right to me. Our pastor visited this site 2-3 months ago and there were around 200 people at that time. All of the people living in this informal encampment are applying for asylum and are awaiting their turn. This is part of Trump’s “wait in Mexico” policy.

Based upon my observation, roughly ½ of the population of the tent-city are young children. It also seemed to me that most of the people were in family groups.

Sanitation and clean drinking water are an obvious concern in these situations. On the day we were there, there were only 4 portable toilets to serve the entire group. There was some water for washing clothes in an area set aside for that purpose, but it was unclear whether this water was drinkable. We delivered bottled water and it was much appreciated.

My impression of the people was that they were remarkably calm, gentle, respectful and glad for our help. Children were everywhere, although there were almost no toys or balls and no place for them to play.

The temperature on the day we were there was in the mid-80s. The people wore light clothing. A bad cold front was expected and we took a few coats across. However, Americans are not allowed to deliver clothing in bulk to the refugees. You can only take what you can personally carry.

During the evening a cold, wet front did hit. This brought temperatures down into the mid-thirties with high wind and rain. Considering the migrants are from the south and that they have few possessions beyond the clothes on their backs, we were very concerned about how they could endure the cold, wet, muddy elements. The weather was also very bad the next day and only slightly better the next.

We took a lunch break and Mike hired a small cocina to cook the rice and beans. During lunch we also bought medicines.

After lunch we served the rice and beans (children 1st, women 2nd, men last). All of the people were obviously hungry, but astonishingly calm and orderly. They were also very grateful. We then delivered the medicines to the medical tents. Again, the people were very thankful.

During the entire time we were at the tent-city, I never saw a single policeman or any evidence of help by the Mexican government or any Mexican aid agency.

Obviously, people have to eat and these people have very little, if any, money. We were told that charitable organizations in Brownsville such as Team Brownsville were taking food across the border. There was no obvious source of food or public cooking facilities near the encampment.

It is important to remember that all of these migrants living in the tent-city are waiting to apply for asylum. They are waiting to tell their story to an immigration officer. If the immigration officer believes they may qualify, they still have to go through more interviews and a formal hearing before an immigration judge in an immigration court.

The Trump administration is strangling the flow of immigrants applying for asylum by what is called “metering.” This means that only a handful of people each day are allowed to walk to the middle of the bridge to speak to an immigration officer. It is a Baskin Robbins ice cream parlor type system. If it is your turn to go onto the bridge, you may have to get up as early as 4 a.m. to get in line and wait your turn. The asylum seekers walk the bridge until they are stopped at a gate. They wait there in line. There is no protection from the elements and they wait for an indefinite period of time. If you miss your turn, your asylum claim is denied.

If the preliminary asylum interrogation results in a denial, you return to Mexico and then, I suppose, go wherever you can go. If the immigration officer determines you are possibly eligible for asylum, you are given a court date, but you are not eligible to wait for your hearing in the U.S. unless you have someone in the U.S. who is willing to sponsor you. Otherwise, you go back into Mexico and wait for a hearing and that hearing could be a very long time in the future. If you miss your hearing, your claim is denied.

Trump has put in place the Migrant Protection Plan. The people at the border simply call it “MPP”. I don’t know who in Washington comes up with these silly, idiotic and ironic names for laws and policies, but there is definitely no “protection” in this policy of making immigrants wait in Mexico or whatever country they first crossed into after leaving their home country. Furthermore, the obvious intent of the policy is to inflict as much misery and hardship upon these people as possible so that it will act as a deterrent to immigration.

Mexico has had its arm twisted to go along with Trump’s policy, but Mexico is doing nothing whatsoever to help these people waiting in Mexico. There was very little, if any, security. There was no shelter other than the tents donated by U.S. citizens. Mexico provides no food, medicine or medical care. Mexico provides very few portable toilets and some running water for washing clothes, but it may not be drinkable. Sanitation is a real problem and an epidemic of some sort is just waiting to happen. It is not an exaggeration to say that the refugees in Syria and Turkey are living in better circumstances than the refugees waiting in Matamoros, Mexico.

It became apparent from our visit and from the explanations we were given that there are two broad, general categories of immigrants and two judicial systems that process them.

As I have described, there are those seeking asylum who have presented themselves at a lawful port of entry and made a request for asylum. The second group are those who have crossed the border at some place other than a lawful port of entry. Of the second group, some are just fleeing poverty; some are trying to get back to family or jobs in the U.S.; and, some are seeking asylum. If a person crosses at any place other than a lawful port of entry and claims asylum, that request is automatically denied and they are arrested. If a person crosses illegally (not at a port of entry) for any purpose and is caught, they are arrested and detained in custody. This is part of Trump’s zero tolerance policy. Crossing at other than a lawful port of entry is a federal crime. If a person is arrested, deported and is caught crossing illegally again, the crime can be a felony. It is common for traffickers to tell immigrants to cross, turn themselves in to the first law enforcement person they see and ask for asylum. That won’t work. Prior policy was that a person could ask for asylum no matter how they got to the U.S., but that is no longer true. We were told by knowledgeable people who have lived their whole lives at the border that unlawful entry was once treated like a traffic offense. You paid a fine and were sent back. However, under Trump’s zero tolerance policy, unlawful entry is treated as a crime and prosecuted as such. People are arrested and held in custody until they go before a judge. It is this policy that leads directly to family separations.

Asylum cases are heard by immigration judges who are actually employed by the Department of Justice and answer to the Attorney General. Spectators are not permitted to witness these hearings. According to the ACLU representative who spoke with us and who is familiar with these proceedings, very few of those seeking asylum are represented by lawyers and the immigration courts are not legally required to appoint lawyers to represent asylum seekers.

We were permitted to watch legal proceedings involving 36 people charged with the federal crime of illegal entry. All were handcuffed and the cuffs were attached to a chain around each defendant’s waist. Of the 36, only one spoke English. All of the defendants wore headphones and communicated through an interpreter.

There was a great deal of security in and out of the courtroom, perhaps more than I have ever seen in any courthouse.

The government was represented by at least 5 and maybe 6 Assistant U.S. Attorneys. This seemed like overkill and waste inasmuch as only one government lawyer spoke during the entire proceedings.

All 36 defendants were represented by a single, court-appointed defense lawyer.

Very few of the defendants were women. The youngest defendant was 18 and the oldest was 50. Almost all of the defendants were in their 20s to early 30s. They looked just like Hispanics you see working in Texas every day. The government lawyer told the judge about each person’s prior criminal record. Very few had ever been arrested. None were rapists, murderers or drug smugglers. The most serious prior offense mentioned was a DWI.

Those who were charged with illegal entry for the first time were given “time served” and deported. Those who had a history of being apprehended more than once were sentenced to additional jail time.

On a few occasions, the appointed defense lawyer very briefly mentioned some possible mitigating circumstance, but it seemed to make little difference in the outcome. Even those who were crossing to get back to jobs they had held for years in the U.S. or who had families in the U.S. were sentenced and deported.

Based upon what the defendants themselves said or what the Court appointed lawyer said, no defendant in the courtroom had more than a 9th grade education and most had much less. Considering that they don’t speak English and have very little education, it is doubtful that they truly comprehended all of the legal proceedings. Nevertheless, it was abundantly clear that they had been caught, jailed, held in detention for some period of time, wanted to be set free, and that answering “yes” to every question was the way to go. All of the defendants were very respectful to the judge. The judge was respectful to the defendants, ran a tight ship, and appeared to be a compassionate man. However, the process was tailored for mass deportations and the result was preordained.

Migrants are deported by taking them in a bus to the bridge and walking them to the center of the bridge. Considering how lightly they were dressed in the courtroom and the cold weather outside when they were deported, I have to assume they had a tough time of it. I have no idea how long they had been in jail before they went to court.

You have heard of family separations and you have heard of what happens when unaccompanied minors are apprehended or surrender to ask for asylum. Mike and Cindy took us to two detention centers. We were not permitted to enter these facilities. One of the facilities was for minors. It was a converted Super Walmart or Sam’s. There had to be at least 150 employee cars in the parking lot, but nobody knows how many children are held there and nobody, not even elected state or federal officials or news media, is allowed inside to observe conditions. It is as if this prison is a CIA “black site”, but it’s in plain view if you know what you are seeing.

The lack of factual, public information about these incarcerated minors is disturbing. Can you imagine a very large group of U.S. children being held in captivity and incognito by government with no accountability? What if U.S. children were being held in a foreign country in secret conditions?

According to the people whom we met who are familiar with the facts, families are separated and, in some instances, they could not be reunited. Precisely how many children are lost in the system, what happened to them and what will happen to them seems to be anyone’s guess. There are many horror stories.

On the bright side, we did visit places that are serving immigrants that are doing splendid work. One is La Posada Providencia. This small residential facility provides temporary quarters for those who are legally in the U.S., but are temporarily without a place to stay while their asylum cases are being processed. It is an oasis and a temporary haven for people. They also help people fill out government paperwork, help make arrangements for travel, help people find lawyers, and help people contact sponsors. If you were a confused, destitute traveler in a strange and inhospitable land, you would want to be here. I can’t say enough good about this charitable organization. Although this organization is affiliated with the Catholic Church, it is not funded by the Catholic Church and must raise its own funds to exist.

Another bright spot is a shelter operated by Catholic Charities across the street from the bus station in McAllen. This is a strategic location because our government was dumping busloads of people at all hours at the bus station or in the border cities. This organization is also supported by other local charitable organizations. They provide meals, clothing, medical care, showers, toiletries, a brief respite, some assistance in making travel arrangements and in explaining where they are, where they need to go and, in general, what is happening.

As I said, the bus station is an important place for immigrants because most of them are traveling by bus. This is a confusing and even dangerous place for a helpless immigrant.

To help immigrants navigate the complexities of their travel and to warn them of the dangers, particularly the dangers of human traffickers and other predators, an organization named “Angry Tias and Abuelas” was created. This name means Angry Aunts and Grandmothers. Their volunteers talk to immigrants at the bus station and discuss the logistics of the travel ahead. They also help with the children and offer sandwiches, comfort, assistance and advice. Imagining myself in a comparable situation in a foreign country with little or no money, I must believe these volunteers are accepted by the immigrants as a Godsend.

Finally, we visited a shelter affiliated with the Methodist Church in Brownsville. This is a smaller version of the shelter in McAllen. It is doing all it can to provide for the immigrants in their time of need, but they also depend on the tireless work of volunteers and donations. I should add that this shelter is also serving the homeless at the same time.

My takeaways from the visit are:

1) There is real suffering at the border. It is not fake news. No one could see it and then deny it;

2) Our government and probably the Mexican government are pursuing a policy of deterrence. By that I mean that they intend to treat people so harshly that they will suffer enough physical, mental and emotional pain that they will not try again to enter the U.S. and they will tell others not to try;

3) Asylum seekers living on the Mexican side of the border at Matamoros are living in wretched, deplorable conditions that will eventually lead to deaths and an epidemic of illness;

4) There are good-hearted, tireless volunteers trying to do whatever they can to make things better for their fellow human beings, but they are fighting a long, hard, expensive, lopsided battle with a short stick and one must wonder how long they can continue;

5) The immigration “crisis” is largely created by our government’s policies.

6) The indefinite detention of minors in secret prisons is abhorrent and should not be tolerated by a free society;

7) What is happening at our southern border is shameful, but entirely predictable and preventable;

8) Some people believe that those claiming asylum are just making up a story to get into the U.S. Before making that judgment, I suggest you meet the people and hear their stories. I also suggest that it’s not reasonable to believe someone would wait in the conditions I saw in Matamoros just for the opportunity to tell a fictitious story to a highly skeptical immigration officer or a judge who has been instructed by his boss to deny asylum claims. Something bad happened to these people that motivates them to endure very difficult circumstances. We owe them the opportunity to be heard;

9) The southern border should not be seen or treated as a hard border. People have been going back and forth for centuries and that will not stop. Whether motivated by family, business, jobs, or other reasons, people will continue to come and go. We are foolish to think we can stop rather than manage the migration of people;

10) The problem is not solved by a fence, thousands of law enforcement personnel, zero tolerance, high technology or a harsh policy of deterrence. As one volunteer said to me, “Don’t ask an immigrant why they are coming to the U.S. If you want to know what motivates them to be here, ask them why they left their country”. If we will ask ourselves why people are leaving Central America and elsewhere, we can better use our resources to address the problems that make them flee rather than to apprehend and deter.

If you are interested in knowing more detail about the asylum system, which is confusing, I have added to this blog a summary which is instructive.

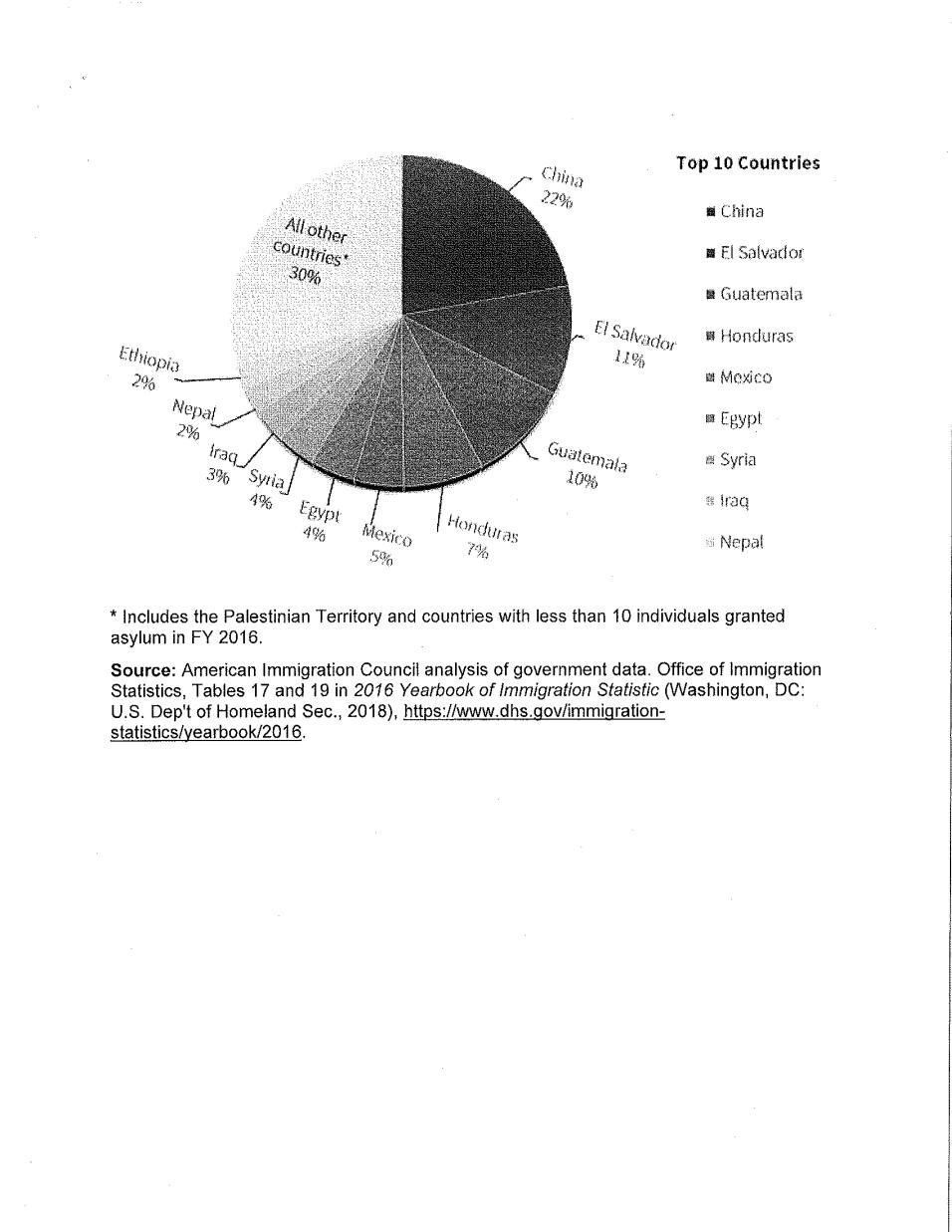

Only 20% of those applying for asylum are successful. Most of the immigrants were from Central America. However, one of the relief agencies we visited had served people from 30 countries.

Whether you are for or against immigration, what I witnessed at the border is not, I hope, a reflection of who we are and what we stand for. We can do better.

Summary: